Goodbye Marcos, For Now

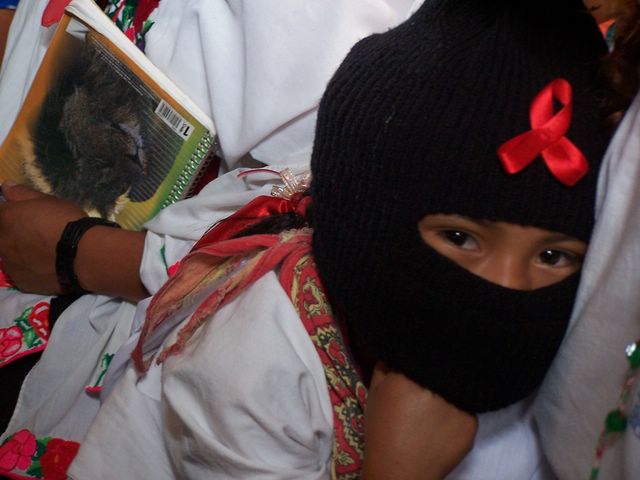

According to Naomi Klein, at the conclusion of last week's international colloquium in memory of Andrés Aubry, Subcomandante Marcos remarked that it would be his last public appearance for some time because of the grave new threat of a counterinsurgent attack against the Zapatista communities.

For those wondering what is going on with the Other Campaign, amongst other things, Marcos gave an illuminating interview at the end of November that was just recently published in the Colombian magazine Gatopardo. Since you can only read that interview in its entirety if you actually pick up the magazine itself, below is my translation of the on-line report from Mexico's El Proceso. With the Womyn's Encuentro beginning today, this report brings us up to speed and also serves as a good follow-up to last year's "Thoughts on Marcos and Leadership" post...

Calderón enlists counterinsurgent attack: Marcos

Protagonismo and attacks against AMLO [the center-left candidate in Mexico’s 2006 presidential elections] have isolated zapatismo, he admits in an interview given to the magazine Gatopardo

Mexico City, December 14. The public reappearance of Subcomandante Marcos in San Cristóbal de las Casa, Chiapas, this past Thursday the 13th, coincided with the publication of an interview in which the Zapatista leader confesses that the movement “is already out of style”; confirms that the government is preparing a counterinsurgency strategy, and says that there is no hunger now in the Zapatista communities and that women play a more important role in the Councils of Good Government.

In addition, he recognizes that the struggle has been worth the trouble, and anticipates that in 2008 the EZLN [Zapatista Army of National Liberation] plans to launch a new form of action that aspires to be, he says, “a new revolution to that of one hundred years ago, not through the armed option but through an other one that junks the political system and refounds the country.”

The interview appears in print in the most recent edition of the magazine Gatopardo. Interviewed by the reporter, Laura Castellano, at the beginning of November, in La Garrucha, Chiapas, Marcos recalls that he and the EZLN were the center of attention in 1994, with the uprising, but recognizes that “we are now out of style.”

It’s like we are in 1993, but the other way around. Then we prepared the uprising without the media and without people [outside support]. Now the government is the one that is preparing the offensive,” he warns.

According to Marcos, the government of Felipe Calderón is preparing a counterinsurgency strategy. In this strategy, he explains, the government has intentionally encouraged polarization locally in giving other indigenous groups land that has been appropriated by the EZLN. “In this way an artificial social conflict is created, cultivated as if in a laboratory, and thus then government forces enter to bring peace.”

The reporter asked him what would be there response in the case of a possible attack, and the Zapatista leader responded that for now they are only taking preventative measures. Nevertheless, he warned that they are not going to remain with their arms crossed.

In the interview, Marcos speaks later of the remarkable overcoming that is actually taking place in the Zapatistas communities, in relation to the absolute marginalization that they experienced before 1994. “It is not that the Zapatista communities are rich, but there is no longer hunger,” he says.

He points out, also, the noticeable drop in the indices of infant mortality and the active participation of women in the Councils of Good Government. “The question of gender begins to concern itself with where resources go,” he emphasizes.

On the decline of the Zapatista movement in the media, Marcos places the beginning of the descent when he made critiques of Andrés Manuel López Obrador, within the framework of the 2006 presidential campaign, which, he says, he took to break with the intellectuals who supported Obrador.

He says that the decision was made during the legislative failure of 2001: “I felt the responsibility and pain of having failed, of not having foreseen what was going to happen.”

Marcos confesses that then the possibility of taking up arms again was considered, but clarifies that after analyzing the situation at great length, they desisted.

He relates, nevertheless, that they decided it was better to break with the political class and intellectuals that supported this [political failure], knowing full well that that was going to isolate them.

In the final part of the interview, the reporter gets Marcos to talk about Marcos.

--Is it a lot of work being Marcos?

The Subcomandante, who accepts that he’s already lost his “little waist”, but even so will agree to pose in exchange for some dollars, responds, sharply: “Yes.”

He explains that the name weighs on him now, that it is a great weight because, he states, (the idea) still prevails that the errors of the EZLN are due to Marcos and the successes are due to the communities.

Marcos mentions that, sometimes, he also feels vulnerable, mainly, he clarifies, when he leaves to [work on] "the Other Campaign." I feel disinclined because it is not my territory, I don’t have the means, my compañeros, the resources…”.

Twenty-four years after having arrived in the mountains of Chiapas, to realize his dreams, Marcos maintains that the struggle has ultimately been worth the trouble. “If I had to do it again, I would do it without changing a thing.” Without finishing the idea he soon makes a clarification: “If I would think of changing something it would be this, that I had not been such a protagonist with respect to the media.”

*

Sunday December 30, 2007, 1:38 pm

Many thanks to activist Dorinda Moreno for passing along these words from tierra_y_vida@yahoogroups.com

from TierrayVida

Subcomandante Marcos fo the EZLN said at a recent gathering in Chiapas:

"I will recommend this book to you. It is this one. The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism, by Naomi Klein. It is one of those books that is worth having in your hands. It is also a very dangerous book. Its danger resides in that it is possible to understand what it says.

As I write this I suppose Naomi Klein has already explained the central axis of what's exposed in her thought, so I won't repeat it. I only note that it deals with aspects of capitalist functioning that

are overlooked or ignored by more than a few theorists and analysts from the left in the world."......

"The signs of war in the horizon are clear.

The war, like fear, also has a smell.

And now we can begin to breathe its stench in our lands.

In the words of Naomi Klein, we need to prepare ourselves for the shock."

According to a communication from the Ministry of the Interior, read out yesterday on the Cuban “Roundtable” TV program, two Cubans perished on Saturday, December 22 after the speedboat in which they were attempting to leave the country capsized one kilometer off the northern coast of Havana province.

According to a communication from the Ministry of the Interior, read out yesterday on the Cuban “Roundtable” TV program, two Cubans perished on Saturday, December 22 after the speedboat in which they were attempting to leave the country capsized one kilometer off the northern coast of Havana province.